Returned after Twists and Turns

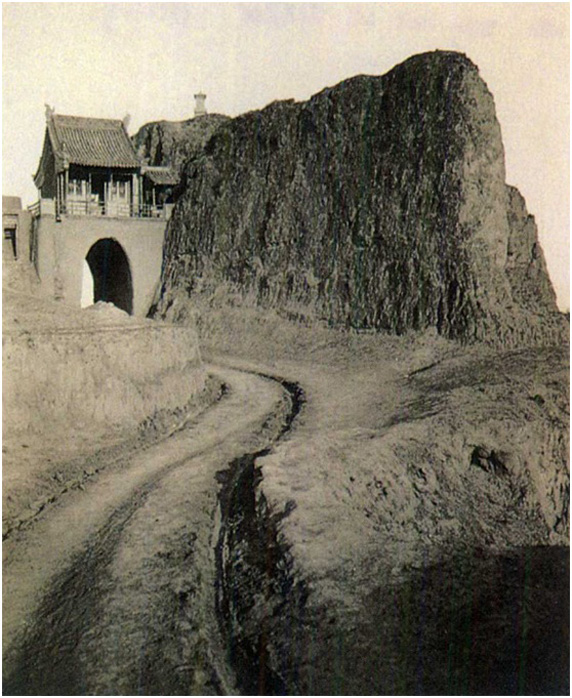

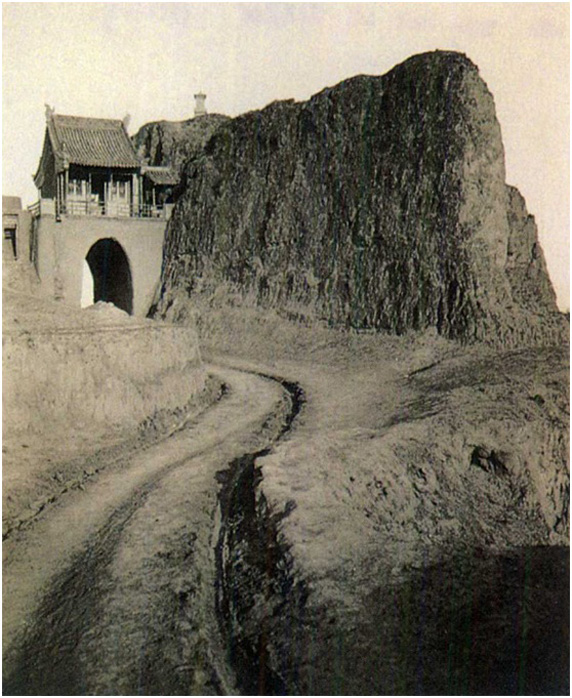

Located in Datong City, Shanxi Province, Hunyuan

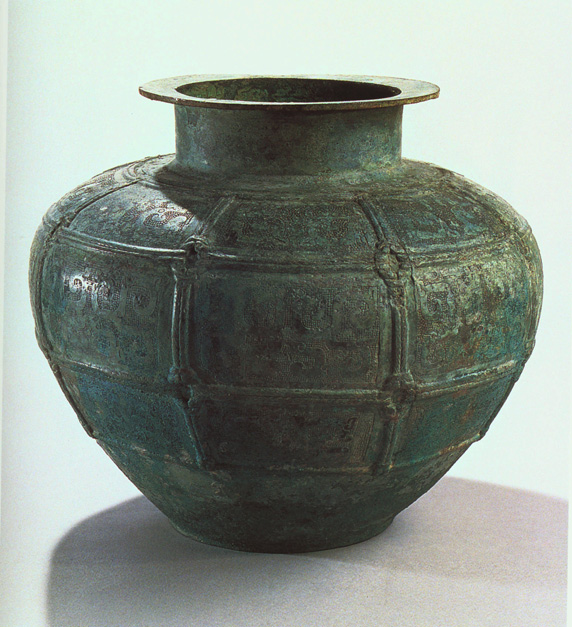

(Group Images 1) got its name for its origin at the tributary Hunhe River of the Sanggan River. On February 28, 1923 Gao Fengzhang and other peasants of Liyu Village of Hunyuan County stumbled upon dozens of bronzes. These objects were in great variety with unique shapes and exquisite decorations, and caused a sensation both at home and abroad, then known as the ‘Hunyuan Sacrificial Vessels’

(Group Images 2)

got its name for its origin at the tributary Hunhe River of the Sanggan River. On February 28, 1923 Gao Fengzhang and other peasants of Liyu Village of Hunyuan County stumbled upon dozens of bronzes. These objects were in great variety with unique shapes and exquisite decorations, and caused a sensation both at home and abroad, then known as the ‘Hunyuan Sacrificial Vessels’

(Group Images 2) This Ox-shaped Zun is one of the most wonderful works.

This Ox-shaped Zun is one of the most wonderful works.

Hunyuan sacrificial vessels were unearthed at the time of constant fighting among warlords in China as well as the time of massive loss of important cultural relics. Their appearance immediately attracted the eyes of domestic and overseas antique dealers. The same year as the findings, French antique dealer Léon Wannieck, who specialized in collecting ancient Chinese arts and crafts, rushed to Hunyuan without delay. However, he arrived at Liyu Village only to find that the County Government had taken a step first and confiscated this batch of bronzes on behalf of the state and exhibited them in the local library.

After having visited the exhibition of bronzes in the library, Léon Wannieck concluded that this group of antique could make a huge profit. Therefore, he made secret investigations in the village and collected more than 20 pieces of bronzes unlawfully possessed by the villagers, and then purchased them at a low price and shipped back to Europe. In 1924, this group of Hunyuan relics made its amazing debut at the ‘Liyu Ancient Bronzes Exhibition’ in the Cernuschi Museum of Paris and won worldwide reputation. Thereafter, these artifacts were sold piece by piece by Léon Wannieck and were scattered over museums of France, the United States, Britain, Germany, Japan and other countries. Among them, the French Guimet Museum alone acquired 15 items and became the museum with the largest collection of Hunyuan relics in the world(Images 3) .

.

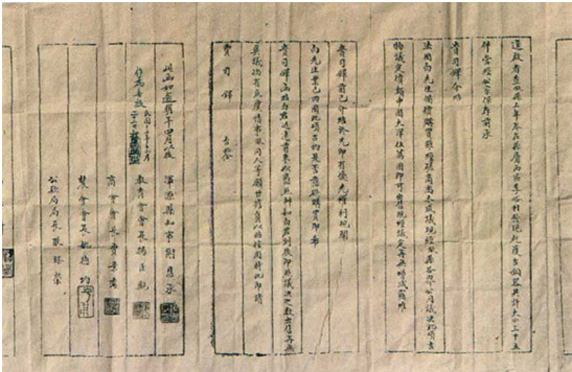

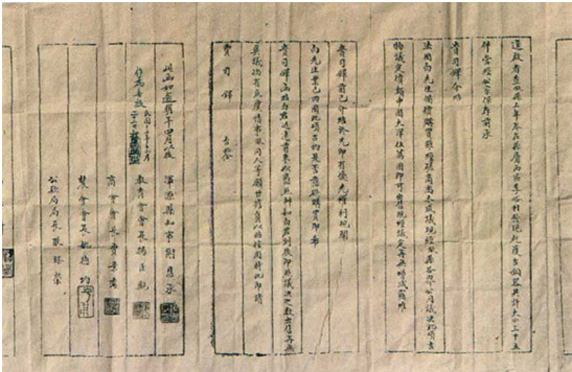

In the same year the Hunyuan County Government, which had confiscated most of the artifacts, organized ‘the Board of Directors for Disposal of Hunyuan Sacrificial Vessels’, and declared to make public auction of these works of art to so called vitalize the rural economy. Léon Wannieck and his agent won the bidding at 50,000 silver dollars and signed a purchase contract(Image 4) .But when they claimed the goods in 1925, to their surprise all of the objects were reproductions. Due to the chaos caused by the unceasing war and varying political situation in China, this auction finally aborted despite protracted diplomatic and legal negotiations.

.But when they claimed the goods in 1925, to their surprise all of the objects were reproductions. Due to the chaos caused by the unceasing war and varying political situation in China, this auction finally aborted despite protracted diplomatic and legal negotiations.

Subsequently, the Board of Directors for Disposal of Hunyuan Sacrificial Vessels decided to make another auction. In 1932, these relics were eventually sold to famous antique dealer C .T. Loo (Image 5) at a high price of 290,000 silver dollars and were housed temporarily at Dadetong Money Shop (an old-style Chinese private bank) in Beijing.

at a high price of 290,000 silver dollars and were housed temporarily at Dadetong Money Shop (an old-style Chinese private bank) in Beijing.

However, with the pressing situation of the anti-Japanese war, coupled with the appeals of Shang Chengzuo and other patriots, C .T. Loo failed to put the relics on the market. Most of them were kept in low key under the smoke of the battle until the victory of the anti-Japanese war.

In 1948, Loo's agent in Shanghai disguised Hunyuan Sacrificial Vessels as ‘antique reproductions’ and shipped them to customs for export, which however was stopped as the press found out the truth and gave it wide publicity. After the repeated appeals of the cultural community in Shanghai, on September 28, 1948, the municipal government sent Yang Kuan, Director of the Shanghai Museum, and research fellow Jiang Dayi to the warehouse of customs for inspection of one case after another. They withheld the relics after registration. This batch of national treasures was finally kept in its motherland after twists and turns.

In 1952, Shanghai Museum was established and the 12 pieces of Hunyuan Sacrificial Vessels including this Ox-shaped Zun were kept in house and became valuable treasures of the museum.(Image 6, flash)

Ox-shaped Zun (wine vessel)

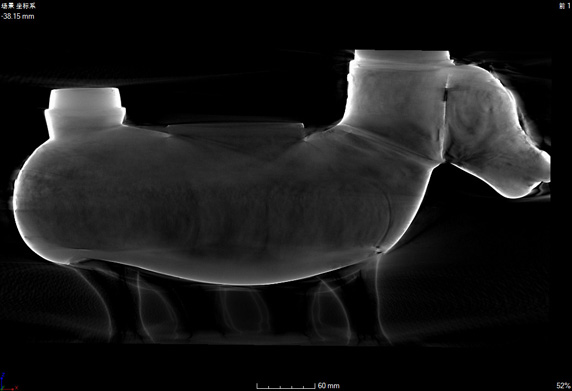

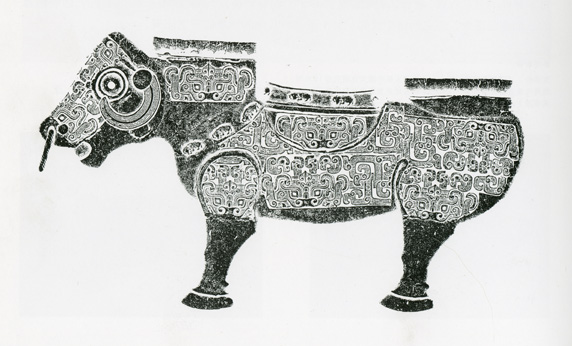

The ox-shaped Zun is the most extraordinary piece of work among Hunyuan Sacrificial Vessels. It is 33.7 cm high, 58.7 cm long and weighs 10.76 kg, cast into the shape of fairly realistic farm cattle (Image 7) . The belly of the buffalo is hollow and there are three holes from its neck to the end of its back. Inside the middle one, there is a removable pot-shaped container. There was a cover on the container when unearthed but now is missing. Judging from its structure, it is a wine warmer. Hot water can be poured into the hollow belly to heat the wine in the pot-shaped container on the back. This particular structured bronze is the only piece of its kind made in the Shang and Zhou dynasties that is kept to date (8: 3D video)

. The belly of the buffalo is hollow and there are three holes from its neck to the end of its back. Inside the middle one, there is a removable pot-shaped container. There was a cover on the container when unearthed but now is missing. Judging from its structure, it is a wine warmer. Hot water can be poured into the hollow belly to heat the wine in the pot-shaped container on the back. This particular structured bronze is the only piece of its kind made in the Shang and Zhou dynasties that is kept to date (8: 3D video) .

.

This work looks dignified with its shape and form designed for practical purpose. It does not completely look like a real ox with its four short legs. But the two powerful horns and wide-open glaring eyes retain the sense of reality (Image 9) , so that the image of the bronze will not appear unreasonable because of its short legs. It can be regarded as the perfect combination of artistic styling and practical use. What attracts the eyes is the cord-like ring at the ox's nose, which indicates that as early as in the Spring and Autumn period, domestication of cattle by piercing the nose had already begun.

, so that the image of the bronze will not appear unreasonable because of its short legs. It can be regarded as the perfect combination of artistic styling and practical use. What attracts the eyes is the cord-like ring at the ox's nose, which indicates that as early as in the Spring and Autumn period, domestication of cattle by piercing the nose had already begun.

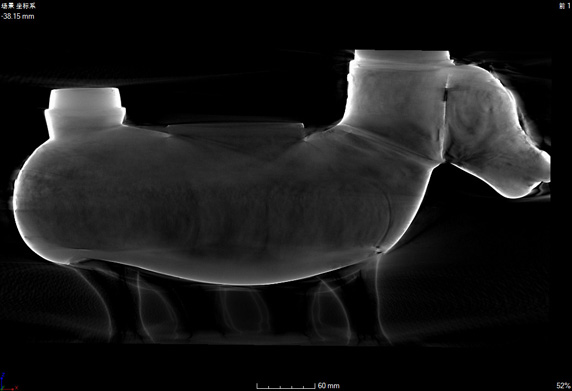

This piece has a very complicated structure, which also means it must have been very difficult to cast. Seen from the X-rays, it should adopt clay piece-mould technique - the prevailing bronze casting technology in the Shang and Zhou periods (Image 10) . The main body of it is cast with the method of integral casting. First sculpture the solid clay model of the object to be cast and fire it to pottery, and then make the hollow outer molds by sections based on the inner mold. Reserve the thickness of the wall of the object according to the needs and assemble the outer molds with the inner one. Then inject the molten bronze from the reserved mouth and the utensil will be ready after it cools down (11: 3D video)

. The main body of it is cast with the method of integral casting. First sculpture the solid clay model of the object to be cast and fire it to pottery, and then make the hollow outer molds by sections based on the inner mold. Reserve the thickness of the wall of the object according to the needs and assemble the outer molds with the inner one. Then inject the molten bronze from the reserved mouth and the utensil will be ready after it cools down (11: 3D video) .

.

Because of the complex shape, this work was welded together after casting in several sections. Some accessories, such as the ring on the nose, were embedded in the principal model after their casting in advance. Though they were cast separately from the main body, they integrated into the whole piece wonderfully without impeding its movability.

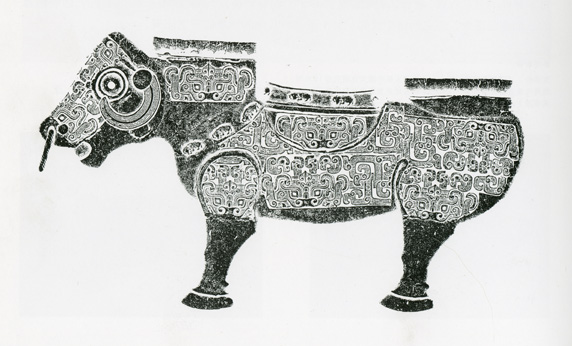

Most of the Hunyuan vessels have sophisticated and delicate patterns in various styles. This piece is finely decorated with animal-mask motif of twisted snake and dragon patterns on its head, neck, body and legs. The composition of the pattern is novel and unique, representing strong characteristics of the times (Image 12) . Meanwhile, pottery fragments with the same patterns were a common occurrence in the Eastern Zhou bronze casting site discovered in Houma, Shanxi province from 1960 to 1961, showing that it is a typical bronze ware of the Shanxi area.

. Meanwhile, pottery fragments with the same patterns were a common occurrence in the Eastern Zhou bronze casting site discovered in Houma, Shanxi province from 1960 to 1961, showing that it is a typical bronze ware of the Shanxi area.

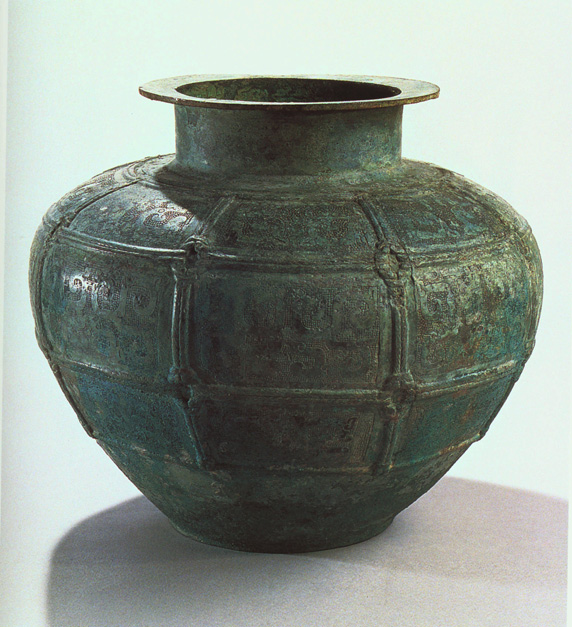

If we take a close look at the pattern on the belly, we can find it has a consecutive double-square structure, which indicates that it was cast with the impression method: using a decorative master mould to stamp out the desired pattern continuously before casting. This method is suitable for batch production of bronzes with the same decorations and was very popular in ancient Shanxi area. The Pot with Bird-and-Animal Design shared the same mould with the Ox-shaped Zun unearthed at the same time for its pattern on its belly (Group Images 13) . And the realistic animal patterns on the intervals of the pot clearly share the same decorative taste with the animal images like tiger and rhino on the neck and the pot-shaped container of the Zun.

. And the realistic animal patterns on the intervals of the pot clearly share the same decorative taste with the animal images like tiger and rhino on the neck and the pot-shaped container of the Zun.

Although the excavation of the Ox-shaped Zun was not the result of scientific archaeological finding, it is likely to be a precious ritual object due to its exquisite appearance. In fact, the name sacrificial Zun itself shows its property as a ritual object.

Zun is an ideograph in ancient Chinese characters, resembling the image of two hands holding a wine vessel offering sacrifice (Image 14) . Therefore, the literatures in Bronze Age usually named the ritual objects dedicated to be used in sacrificial ceremonies as ‘Zun Yi (sacrificial vessels)’. People in the Song dynasty also called the tall and big wine containers as Zun (Group Images 15)

. Therefore, the literatures in Bronze Age usually named the ritual objects dedicated to be used in sacrificial ceremonies as ‘Zun Yi (sacrificial vessels)’. People in the Song dynasty also called the tall and big wine containers as Zun (Group Images 15) , and it has been in use to date since. Among the bronze wares, a type of wine vessels for ritual ceremony that simulated birds and animals (Group Images 16) is also called zun. The character Xi in ancient times was the umbrella term for the livestock used in sacrifices, thus this kind of objects was traditionally called as Xi Zun. In addition, the cattle-shaped Zun among those in the shape of birds or animals is also specially called Xi Zun, which this piece of work belongs to.

, and it has been in use to date since. Among the bronze wares, a type of wine vessels for ritual ceremony that simulated birds and animals (Group Images 16) is also called zun. The character Xi in ancient times was the umbrella term for the livestock used in sacrifices, thus this kind of objects was traditionally called as Xi Zun. In addition, the cattle-shaped Zun among those in the shape of birds or animals is also specially called Xi Zun, which this piece of work belongs to.

Ox-shaped Zun is frequently recorded in literature as ritual objects in sacrificial ceremonies and banquets. According to Rites of Zhou - Minister of Rites - On Ritual Objects, animal-shaped Zun of different types are used for different ceremonial occasions in spring, summer and ancestral offerings as well as other important rituals.

In Book of Songs - Song of Lu - Bi Gong, there is the description of Duke Xi of Lu making sacrifice to the newly built Ancestral Hall, in which he used white, red and other large and tall animal-shaped Zun. The scene was solemn and grand.

Poems of the Song and Ming dynasties also mentioned the scenes of offering sacrifice with Ding, Lei, Bian, Dou and other ritual objects, which shows the powerful continuity of this tradition.

Copyright 2008-2015 Shanghai Museum

Excavation Site Map of the Ox-shaped Zun

Between 40° north latitude and 114° east longitude, and located in the middle and upper stream of the tributary Hunhe River of the Sanggan River, Hunyuan County is subordinate to Datong City, Shanxi Province. It borders Guangling in the east and Yingxian County in the west, and Lingqiu County and Fanzhi County in the southeast with Hengshan Mountain as the division line, connecting with Datong County and Yanggao County in the north by Liulengshan Range. It was under the rule of the State of Dai during the Spring and Autumn period. The Northern Wei relocated its capital to Pingcheng (now Datong), and Hunyuan County became the environs of the capital. The county has been called Hunyuan since the Tang dynasty.

Gatehouse of Hunyuan County

The Overall Image of the Ox-shaped Zun (Angle A)

It remains unknown about the burial situation of Hunyuan Sacrificial Vessels before the excavation. Some suggested they were hoarding, while others thought they were burial objects of the nobles. These vessels are sleek in shape, sophisticated in technology, and unique in decoration, which integrate the style features of Jin (Shanxi) areas, Yan (Hebei) areas and northern ethnic minorities. They were supposed to be in the procession of the State of Dai founded by the Beidi Tribe during the late Spring and Autumn period.

Hu (wine vessel) with Bird, Animal and Dragon Design

It is a wine vessel in two pieces. There might have been a big and tall cover and a pair of dragon ears, but these are lost now. It is covered with delicate patterns. There are four wide stripes of patterns from the rim to the bottom. The first three are the interlocking images of coiled dragons and beasts with human head and bird tail. The pattern on the fourth belt has the same animal-mask motif as that on the Ox-shaped Zun. Between the intervals of the patterns, there are realistic design of rhinos and birds and other animals with lifelike forms and detailed hair and skin, reflecting the high level of bronze cast technique during that period.

Dou (food vessel) Inlaid with Hunting Scenes

This vessel, with copper inlaid decoration all over the body, displays a hunting scene which vividly recording the specific hunting situations of the ancient nobilities. Decorations showing human figures only appeared after the late Spring and Autumn. Regular and symmetric pattern began to be discarded. The free composition and smooth lines laid the groundwork for the development of portrait art of the Han dynasty.

Dou (food vessel) with Four Tigers and Coiled Dragon Design

This piece of work contains two pieces, with exactly the same styling and patterns, housed in Metropolitan Museum of Art and Shanghai Museum respectively. The piece in Shanghai Museum was 15.6 cm high with its original stem missing. In 1980, a foot with tile design according to the piece in Metropolitan Museum was reassembled on the container. The height reached 26.4 cm after the restoration. The lower part and the cover on top form a depressed sphere. With the big round handle, the cover can be put upside down to hold things. The outer wall of the vessel is quartered, with each division decorated with a climbing tiger of lively and vivid shape.

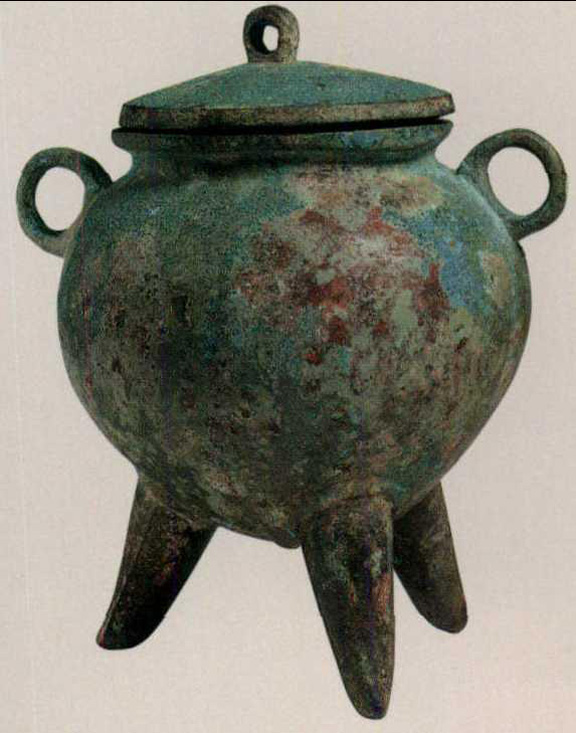

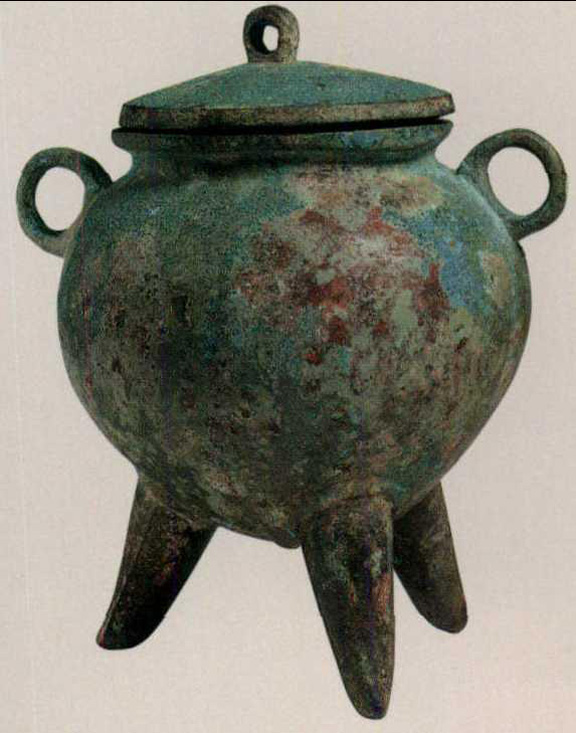

Ding (food vessel) with Coiled Snake Design

This round shaped vessel has a ring knob on the center of cover with a loop cast separately. There are three crouching tigers around the body in trisection. The cover and the body are decorated with the fine, exquisite and also neatly arranged coiled snake patterns in flat carving. This kind of decoration is the typical style of the bronzes produced in Jin (Shanxi) areas during the middle and late Spring and Autumn period.

Ding (food vessel) with Inlaid Dragon Design

This piece of work is 17.5 cm high. On its flat cover with folded rim stand three heads of deer with a ring knob in the center. The cover and the belly are decorated with animal motif outlined with copper. The decorations are divided into two rows connecting with each other. The upper part of the foot is decorated with animal-mask motif, and delicate turquoise is used for the eyes of the animals, providing the finishing touch to the work.

Dui (round or oval vessel with a lid for holding cereals) Inlaid with Animal Pattern

There is a ring shaped ear and three three-dimensional bird heads on the top of the cover. The cover and the belly part are decorated with tiger-shaped design inlaid with pure copper. Its ears and ring foot are also inlaid with geometric patterns and animal design of pure copper. In bronze wares Dun, articulated as Dui, is a specifically designed food container for holding millet, rice, sorghum and other staples.

Ling (wine vessel) with Double Dragons and Net Design

Ling is a wine vessel. This piece of work is decorated with net pattern from shoulder to belly and exquisite design of two dragons inside, interlocking with each other. The entire pattern sets against the background of well-arranged dots, looking especially delicate. The net pattern on bronze takes after the design of knotted cord of the pottery, which is generally knotted with two parallel connected cords. This kind of pattern is usually decorated on the surface of the wine or water containers, with no practical significance. It is just a simple, elegant decoration method prevalent during the periods of Spring and Autumn and Warring States.

Ding (food vessel) with Ring Ears

This work with unique and simple shape is drastically different from the bronze styles of the Central Plains at the time. It is the outcome under the influence of the bronze style of the northern ethnic minorities, and one of the most unique bronzes unearthed in Liyu Village.

Hu (wine vessel) with Inlaid Bird-and-Animal Design

There are two copper handles with rings on the cover and neck respectively. The neck of the vessel is inlaid with two lines of bird-like pattern of red copper; the belly is also inlaid with two lines of animal-shaped pattern in pure copper. It shares similar style with Yan (Hebei) bronzes. In 1959, it was collected and exhibited by National Museum of Chinese History (today’s National Museum of China).

Guimet Museum in France

Auction Contract in 1925

C .T. Loo

C .T. Loo (1880-1957), was born in Huzhou of Zhejiang province. He lived abroad in France and the United States successively. He was a world famous antique dealer and notable curio dealer in the early 20th century. He trafficked many Chinese national treasures abroad, including some of the greatest masterpieces in the history of Chinese art, such as the stone carvings of Sa Lu Zi (a valiant, purple looking horse) and Quan Mao Gua (curly haired yellow horse with black mouth) of the Six Gallant Horses of the Zhaoling Mausoleum.

The Overall Image of the Ox-shaped Zun (Angle B)

Close-up View of the Head of the Ox-shaped Zun

X-ray Perspective of the Ox-shaped Zun

Rubbing of the Ox-shaped Zun

Close-up View of the Belly Part Patterns of the Ox-shaped Zun

Close-up View of the Belly Part Patterns of the Hu with Bird, Animal and Dragon Design

Glyph of the Chinese Character, Zun, in the Inscriptions on Ancient Bronze Objects

Zun (wine vessel) with Animal-mask Design, Shang (16th - 11th century BC)

Zhui Fu Gui Zun (wine vessel), Late Shang (13th - 11th century BC)

Rabbit-shaped Zun (wine vessel), unearthed at Marquis of Jin Tomb in Shanxi province

Bird-shaped Zun (wine vessel), unearthed at Marquis of Jin Tomb in Shanxi province in 1992

got its name for its origin at the tributary Hunhe River of the Sanggan River. On February 28, 1923 Gao Fengzhang and other peasants of Liyu Village of Hunyuan County stumbled upon dozens of bronzes. These objects were in great variety with unique shapes and exquisite decorations, and caused a sensation both at home and abroad, then known as the ‘Hunyuan Sacrificial Vessels’

(Group Images 2)

got its name for its origin at the tributary Hunhe River of the Sanggan River. On February 28, 1923 Gao Fengzhang and other peasants of Liyu Village of Hunyuan County stumbled upon dozens of bronzes. These objects were in great variety with unique shapes and exquisite decorations, and caused a sensation both at home and abroad, then known as the ‘Hunyuan Sacrificial Vessels’

(Group Images 2) This Ox-shaped

This Ox-shaped  .

.

.But when they claimed the goods in 1925, to their surprise all of the objects were reproductions. Due to the chaos caused by the unceasing war and varying political situation in China, this auction finally aborted despite protracted diplomatic and legal negotiations.

.But when they claimed the goods in 1925, to their surprise all of the objects were reproductions. Due to the chaos caused by the unceasing war and varying political situation in China, this auction finally aborted despite protracted diplomatic and legal negotiations.

at a high price of 290,000 silver dollars and were housed temporarily at Dadetong Money Shop (an old-style Chinese private bank) in Beijing.

at a high price of 290,000 silver dollars and were housed temporarily at Dadetong Money Shop (an old-style Chinese private bank) in Beijing.

. The belly of the buffalo is hollow and there are three holes from its neck to the end of its back. Inside the middle one, there is a removable pot-shaped container. There was a cover on the container when unearthed but now is missing. Judging from its structure, it is a wine warmer. Hot water can be poured into the hollow belly to heat the wine in the pot-shaped container on the back. This particular structured bronze is the only piece of its kind made in the Shang and Zhou dynasties that is kept to date (8: 3D video)

. The belly of the buffalo is hollow and there are three holes from its neck to the end of its back. Inside the middle one, there is a removable pot-shaped container. There was a cover on the container when unearthed but now is missing. Judging from its structure, it is a wine warmer. Hot water can be poured into the hollow belly to heat the wine in the pot-shaped container on the back. This particular structured bronze is the only piece of its kind made in the Shang and Zhou dynasties that is kept to date (8: 3D video) .

. , so that the image of the bronze will not appear unreasonable because of its short legs. It can be regarded as the perfect combination of artistic styling and practical use. What attracts the eyes is the cord-like ring at the ox's nose, which indicates that as early as in the Spring and Autumn period, domestication of cattle by piercing the nose had already begun.

, so that the image of the bronze will not appear unreasonable because of its short legs. It can be regarded as the perfect combination of artistic styling and practical use. What attracts the eyes is the cord-like ring at the ox's nose, which indicates that as early as in the Spring and Autumn period, domestication of cattle by piercing the nose had already begun. . The main body of it is cast with the method of integral casting. First sculpture the solid clay model of the object to be cast and fire it to pottery, and then make the hollow outer molds by sections based on the inner mold. Reserve the thickness of the wall of the object according to the needs and assemble the outer molds with the inner one. Then inject the molten bronze from the reserved mouth and the utensil will be ready after it cools down (11: 3D video)

. The main body of it is cast with the method of integral casting. First sculpture the solid clay model of the object to be cast and fire it to pottery, and then make the hollow outer molds by sections based on the inner mold. Reserve the thickness of the wall of the object according to the needs and assemble the outer molds with the inner one. Then inject the molten bronze from the reserved mouth and the utensil will be ready after it cools down (11: 3D video) .

. . Meanwhile, pottery fragments with the same patterns were a common occurrence in the Eastern Zhou bronze casting site discovered in Houma, Shanxi province from 1960 to 1961, showing that it is a typical bronze ware of the Shanxi area.

. Meanwhile, pottery fragments with the same patterns were a common occurrence in the Eastern Zhou bronze casting site discovered in Houma, Shanxi province from 1960 to 1961, showing that it is a typical bronze ware of the Shanxi area. . And the realistic animal patterns on the intervals of the pot clearly share the same decorative taste with the animal images like tiger and rhino on the neck and the pot-shaped container of the

. And the realistic animal patterns on the intervals of the pot clearly share the same decorative taste with the animal images like tiger and rhino on the neck and the pot-shaped container of the  . Therefore, the literatures in Bronze Age usually named the ritual objects dedicated to be used in sacrificial ceremonies as ‘

. Therefore, the literatures in Bronze Age usually named the ritual objects dedicated to be used in sacrificial ceremonies as ‘ , and it has been in use to date since. Among the bronze wares, a type of wine vessels for ritual ceremony that simulated birds and animals (Group Images 16) is also called

, and it has been in use to date since. Among the bronze wares, a type of wine vessels for ritual ceremony that simulated birds and animals (Group Images 16) is also called